It might seem strange to open this essay by speaking about circulation and vitality in regard to Daesh. Yet when we think of a nation-state, circulation is rarely the first thing that comes to our minds. Imagine a room where air doesn’t circulate well. Think of that stale, musty smell. Perhaps blood flow in the body might best encapsulate the importance of circulation, for once blood stops flowing the person will die. In a more tangible sense, states deliberately construct and maintain infrastructure to facilitate circulation of goods and people- think railroads, freeways, and postal systems, among others. Despite this importance, circulation is rarely part of how states are analyzed. Instead, territory, language, shared history, culture, religion, and central governments have all been part of how we most often try to think about nations and nation-states. But is Daesh a state, you ask? While many have been loathe to recognize it as such, the way it conducts itself inside the areas it governs cannot be called anything but a state. As Leif Stenberg pointed out in a seminar I was part of at the CMES Lund University, the Islamic State is perhaps more of a state right now than either Iraq or Syria.

It is not just among scholars and journalists that questions of statehood and territory have been important. Jihadists have been arguing vehemently amongst themselves for years about these very questions. Since the mid 90’s, many jihadists were eager to seize territory, some were actually willing and able, while others remained convinced it was a bad idea if they couldn’t actually hold it. This split arguably was central to the difference between ISIS and Al-Qaeda: where Al-Qaeda veterans were often unwilling to seize territory and pointed to the failures to govern or hold territory, ISIS refused to listen, seized territory, and declared “the caliphate” to much “success”. Al-Qaeda’s approach most definitely changed after the emergence of Daesh, as can be seen in Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria. Recently released documents show that Osama Bin Laden remained against seizing territory up until his death and warned an Islamic State would fail. Instead of asking about how ISIS views the concept of seizing territory, in abstract, I want to explore the reality on the ground, especially through the lens of circulation- who moves in Daesh territory? How do they do it? What kinds of movement does Daesh facilitate and what kinds does it control? While the group’s motto of sorts is الباقية و التمدد, meaning “remaining and expanding”, the issue of circulation is seemingly ignored. I will argue that Daesh must prioritize circulation because of structural constraints on its ability to act like a state in the international arena.

Daesh Statebuilding: A lot of scraps, necessary imports, heavy doses of violence

First, Daesh isn’t building a state from scratch. They aren’t even building institutions from square one, but rather drawing on a wide variety of existing institutions and infrastructure. Some of these include dams, roads, oil fields, schools, prisons, and border crossings. Daesh has benefited handsomely from seizing military materiel and arms too. Since it grew in strength in fog of the Syrian War, especially in late 2013 and early 2014, Daesh has been successful at attacking and seizing many of these kinds of existing infrastructure. It has destroyed others, and it has strategically withdrawn from territory when necessary. The group also has benefitted from a lot of institutional knowledge, getting key individuals to bring their skills from the Iraqi state with them. We need to be willing to place ourselves in their shoes to try to understand their approach, and I definitely don’t mean that to justify the way they treat people, but rather their strategic thinking. Rather than a set blueprint based on ideology, Daesh’s actions fit a very different template, one that is primarily geared toward ensuring circulation. I mean that Daesh seems to have sized up what already existed in terms of assets and infrastructure, and made decisions about what territory it could go after and why, rather than attempting to seize as much land as possible. Daesh especially valued roads which are vital to its ability to move goods and people.

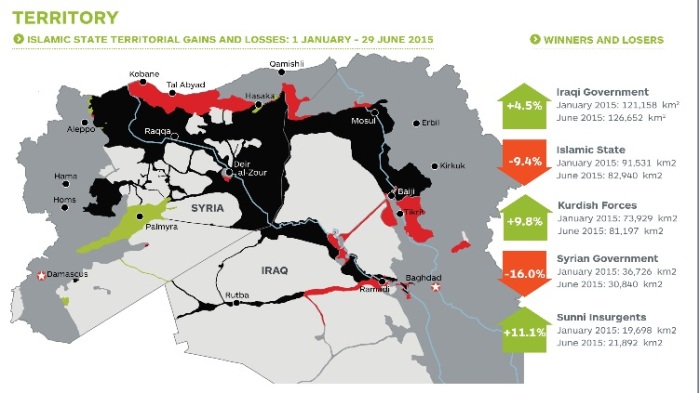

map courtesy of IHS Jane’s

Beginning in early January 2014, while Daesh was increasingly operating in Iraq to seize areas in Anbar, it had to withdraw from multiple regions of Syria during intense fighting with other rebel factions. Daesh lost control of multiple municipalities in these first two weeks, but made efforts to hold on to Raqqa (Lister 2015, 90). It likewise concentrated efforts on keeping a number of areas close to the border with Turkey, like al-Bab, Jarablus and Manbij (Lister 2015, 194). These three are marked in the interactive map below.

While there were strategic withdrawals at this time, Daesh also succeeded in capturing all of Raqqa in January ’14, forcing Jabhat al-Nusra and Ahrar al-Sham out of the city after intense fighting (Lister 2015, 195). By mid-March 2014, Daesh had withdrawn from Latakia, Idlib, and western Aleppo (Lister 2015, 208), concentrating as mentioned before in Manbij, Jarablus, and Raqqa. It would not give up on the areas it withdrew from, apparently aiming to connect territories it had conquered. It largely conquered the areas between Raqqa and Deir al-Zour, and on towards the border town of albuKamal. Its seizure of Mosul in June 2014 shocked the world, but apparently it shouldn’t have. As has been shown throughout the conflict, the border with Turkey is a real lifeline for the group. If Daesh was truly unable to benefit from circulation of goods and people through this border, it would shrivel and eventually die. It would have to establish a second major supply route, and its not clear where that would come from in its immediate vicinity. Mountainous territory to its north and east combined with harsh deserts to the south west are formidable barriers to effectively moving goods or newly-arriving jihadis. But what about inside the areas it has consolidated? How does the organization manage the movement of people and goods?

Circulation and Distinction inside Daesh Territory

Inside of Syria and Iraq, there have been movements of people brought about by the extreme violence since the arrival of Daesh. In Syria, many fled areas gripped by war and went either to areas captured by Daesh or areas under firm control of the regime. We shouldn’t assume this split follows religious or ideological lines, most likely moved as quickly as possible, seeking shelter and stability. Daesh actually claimed that many farmers came to its territories because they were escaping the violence and robbery that plagued them outside. In doing so, it explicitly presents itself as a place of refuge for Muslims. That theme stretched more broadly to other propaganda released which denounced refugees who fled the war for Europe or other parts of the West, since Daesh wanted them to come join the Caliphate. Their unwillingness to do so doesn’t reflect well on the image Daesh works so hard to polish and present, a key part of attracting more recruits from abroad. Finally, Daesh has equated moving out of the territory with apostasy, so people literally have to escape clandestinely. Whereas the organization is willing to strategically withdraw from territory when necessary, it has shown itself unwilling to let those who have joined leave with their lives, if it can help it.

To operationalize this control of movements in and out of the territory they occupy, Daesh has a department that specifically handles questions of border management. The organization controlled the Tal Abyad border crossing for some time, and it made it far easier for them to facilitate passage in and out. Several bus companies based in Raqqa and Mosul opened up which serviced this route. Asma, interviewed in the NYT, described her role in the Al-Khansaa Brigade, where she would travel to the border to meet new female recruits and bring them back to Raqqa. Women experience significant limitations on their movement. It has been decreed that women are not to travel without a male guardian, or mahrim.

Checkpoints distributed throughout Daesh territory serve to control internal movement, and passes have been developed to regulate the differential ability of some individuals to move more freely, or even leave the territory without being labeled an apostate. For example, one citizen of the “Caliphate” got this permission slip to travel to Kuwait ( see Tamimi Archive, 2J). Another document demonstrates official permission given to a member of the Shaitat tribe to return to his home. This needs to be read in the context that Daesh seizes the property of those who flee, and also in light of the revolt by this tribe which was crushed by Daesh, resulting in the deaths of several hundred of its members. As the document is undated, it is unclear if it predates or postdates the Daesh massacre of members of the same tribe. In this same vein, Daesh did not want its soldiers moving around as they please, so it posted this sign telling truck drivers NOT to give them rides:

No matter how much they might deny it, there is something very imposed and foreign about Daesh. In a weird reversal, the foreigners inside Daesh territory have status and power. This is part of a peculiar hierarchy inside the organization, where many of the top echelon are all ex-Ba’thists, but besides this, foreigners generally enjoy a privileged status inside the “Caliphate”. Several interviews with people who left have all testified to this hierarchy, and it apparently privileged foreigners in things as diverse as salary, internet access, and freedom of movement. A recent report from Mosul described how a foreign fighter in Daesh accosted an old Iraqi man for having trimmed his beard too short, and the man was in no mood to listen, shouting back. Six Iraqi Daesh fighters intervened on the old man’s behalf, and beat the foreign fighter who had accosted him, throwing him into their car and driving away. Daesh also took steps to keep the two groups apart:

“But both within their unit and more broadly across Raqqa, the Organization had issued a strict decree: No mingling between natives and foreigners. The occupiers thought gossip was dangerous. Salaries and accommodations might be compared, hypocrisies exposed.” (NYT -ISIS Women and Enforcers in Syria Recount Collaboration, Anguish and Escape 11/21/15)

Daesh did attempt to paper over this division by getting some new arrivals to symbolically burn their passports upon arrival. Afterwards, however, they seem to have realized the value of these passports and they stopped burning them, and instead kept them at the HR department. Just as happens in other parts of the world, it is far easier to use a real passport of someone you resemble than it is to counterfeit it completely. Especially for countries with chips that scan digitally, producing fake passports can be very difficult. Reports have also emerged that Daesh has the ability to make new Syrian, Libyan and Iraqi passports, though this comes from government sources who have provided no independently verifiable proof this is true. Circulation needed to be facilitated in ways beneficial to the state, and controlled in those it deemed dangerous. At the same time Daesh must facilitate the movement of oil both within and outside of its territories. These exports are vital sources of revenue. The map in this report by FT about the Daesh oil trade is the best one I have seen, and it shows the supply routes the oil follows in detail. Finally, a great new investigation about the supply chains of parts used by Daesh to make car bombs shows just how globalized it really is, drawing on 51 companies from 20 countries.

It All Comes Back Around to Circulation

After the key victory in late 2015 which saw the Kurdish YPG retake control of Sinjar, Daesh struggled to continue to move goods and people as it had before. Daesh immediately began trying to create a new connection, not only by fighting to regain control but by building a new road. A new path through the desert was actually found by truck drivers, reconnecting Mosul with Raqqa, showing the vital importance of this connection to Daesh and the people who live in Mosul, especially. There is no other major trade route to get basic goods into Mosul because of how it is isolated from Baghdad, and Daesh is dependent on the Turkish border as has been outlined.

Most recently, Daesh lost control of Shadadi in northeastern Syria, another key city linking Syria and Iraq. As can be seen on the map it is due west of Sinjar. Not long after the ceasefire was implemented across Syria, Daesh tried to seize the Tal Abyad border crossing between Syria and Turkey which it lost to the Kurds. Because of the long and porous nature of the border between Turkey and Syria, goods from Turkey have not been completely cut off to Daesh, as smugglers find other ways, but control of that central artery clearly helps facilitate circulation. Daesh still controls some of it to the west much closer to Aleppo, but the Kurds have control of the border on the Syrian side in the entire northeast of the country. Blood is still moving in the Daesh circulatory system, but not as efficiently as before. There have been rumors that Daesh actually wants to seize parts of northern Lebanon (Akkar) to access the Mediterranean, something that American and Lebanese military planners are anticipating and planning for. If Daesh could operate a functioning port, it would fundamentally change what it can get to its territories and spread the clashes between its fighters and foreign nations onto the Mediterranean Sea.

A Permanently Incomplete State?

At this point, some of you might be thinking, everyone wants to control supply routes during a war. Nations and their borders are born out of wars and violence that break down and reconstitute networks of violence. The networks that are successful in establishing a hegemony on the use of coercive violence in a territory can potentially solidify into a state. Isn’t that what you’re outlining here? Yes, yes and yes. The difference is that at this point, Daesh is stuck in an in-between ‘state’- it constitutes a state in important ways but doesn’t (and can’t any time soon) in other crucial ways. It’s not an army fighting on behalf of a state to preserve an existing state, but rather one trying to leech vital elements out of two crumbling states (Iraq and Syria) and cobble them together into a new one. They produce tons of shiny propaganda in a litany of languages to draw new fighters, because that’s necessary. Just as they need a flow of goods from outside, they need a constant, renewing flow of fighters. They have been pushing fighters NOT to have kids; the organization worries that they’ll be unwilling to carry out suicide missions if they get attached to new families. Thousands of their jihadis have died and others have left, disillusioned. They can tax the population heavily in the areas they control, but they cannot effectively conscript them. Where other nation-states are dependent on migration for labor, Daesh depends on it for fighters, because it exists in a constant state of war. Moreover, many fighters are killed or incapacitated and the state experienced significant brain drain, especially among doctors. All of these issues compound the fact that they’re limiting expansion of the population through birth control. Daesh needs new fighters and skilled workers to travel to join them, and this movement can only effectively come from Turkey south into Syria.

The problem with all of the above is that Daesh remains too unstable to begin policies meant to stimulate any growth in the manner other states can. These battles to control key arteries will only keep circulation flowing, they will not stabilize the “caliphate”. As pointed out above, Daesh apparently has the ability to make Syrian and Iraqi passports, but not their own that will be recognized internationally. This is representative of where they stand, effectively constituting a state but unable to finalize a number of details that other states can to participate in the global economy. Just as it struggles with passports,neither can it make an internationally recognized currency, despite its attempts to do so. A currency that cannot be exchanged for other currencies is fatally fragile. I think that was exactly why they insisted on using gold and silver, because those metals have value independent of the state.

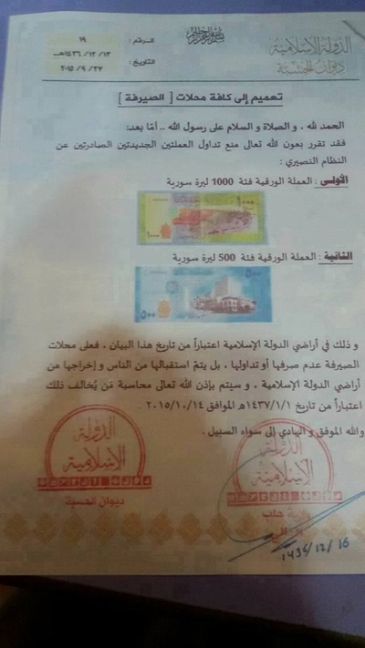

Yes, they claimed it was about undermining Western economic hegemony, but I think it was much simpler than that. Their minting of coins apparently fell apart after its presses were seized (in southern Turkey no less) and reports since have no more use of the gold and silver coins. That means it remains dependent on foreign currencies, especially American dollars, Iraqi dinars, and Syrian dinars to use as currency in its territories. This dependency is demonstrated in an administrative decree from 30 September 2015 where Daesh informs all shopkeepers not to accept or circulate new 500 and 1000 Lira notes from the Syrian government. It seems to me, again, to be a feeble policy meant to control money supply in a state that can’t actually print its own money. Absent these abilities, Daesh is even more dependent on circulation it can facilitate of goods and fighters.

Thus, the unique situation of permanent war circumscribed by a variety of factors fundamentally limits Daesh in Iraq and Syria. Even if they can keep circulation flowing and new recruits coming, it is an unsustainable venture as is. I have no way of predicting how long it will last, I don’t think anyone does, but absent a fundamental transformation in the factors described above, I don’t see any way Daesh can overcome these limitations. More broadly, they can potentially develop statelets in other parts of the world, as they are already beginning to, but I don’t see those becoming anywhere near as developed as the base in Syria and Iraq.

I would like to thank Spyros Sofos for expanding my thinking in regard to these topics! The quick discussion of the argument inside Al-Qaeda about seizing territory is a nutshell distillation of William McCants’ work, find my full review of it here.

Great post as always Michael.

“questions of statehood and territory have been important. Jihadists have been arguing vehemently amongst themselves for years about these very questions. Since the mid 90’s, many jihadists were eager to seize territory, some were actually willing and able, while others remained convinced it was a bad idea if they couldn’t actually hold it. This split arguably was central to the difference between ISIS and Al-Qaeda:”

I think it’s important to point out that this question is really about a tactic. A means, not an End.

And the history of violent reform movements (which is what both ISIS and AQ are), is shifts back and forth between different tactics, based on perceptions of what works.

Bin Laden wasn’t philosophically opposed to holding territory on some fixed, never changing moral principle.

He was against it because based on the info that was available to him, he thought it would be futile. All evidence from his formative experience (for example, Egyptian Jihadist groups from the 1970s through 1990s) would suggest that to be the case.

But its doubtful he could have imagined the trajectory of the Syrian Civil War and the opportunity it may have opened up for Jihadists. And if he was alive today, it’s just as likely he might have issued some press release from his deep hiding saying something like “Circumstances have changed; these guys are doing something worthwhile. I give them my blessing.”

Extremist movements always have violent disagreements over tactics and they almost always change, based on perceptions of what will work. Nothing Jihadists are arguing about is any different than what past radical reform movements fought over.

The Nazis gave up violence for a period of time after their failed Beer Hall Putsch. They went the legal route – not because they were suddenly opposed to violence, but purely out of tactical calculation.

Everyone thought Lenin was crazy to sieize power in 1917. Nothing in Communist thinking said “Russia is where the Rev is going to take place.” Everyone thought it would be Germany. But he said there is an opportunity, it has to be taken. Not unlike ISIS with the sudden unforseen opportunity in Syria.

Stalin gave up World Revolution in 1927 to just focus on Russia, because they had no chance of real success.

LikeLike